As our company policy, we certify all our development projects with green certification from the Indian Green Building Council.

Green Certification often gets a bad reputation as it is a standardized platform of measuring sustainability across various cultures and geographies. We follow the system as we find it to be a good way to keep ourselves accountable to the various aspects of sustainability from the very start of the design process. Certification forces us to keep detailed accounts, and make accurate calculations such that our sustainable efforts are not only in name but are real with measurable impact.

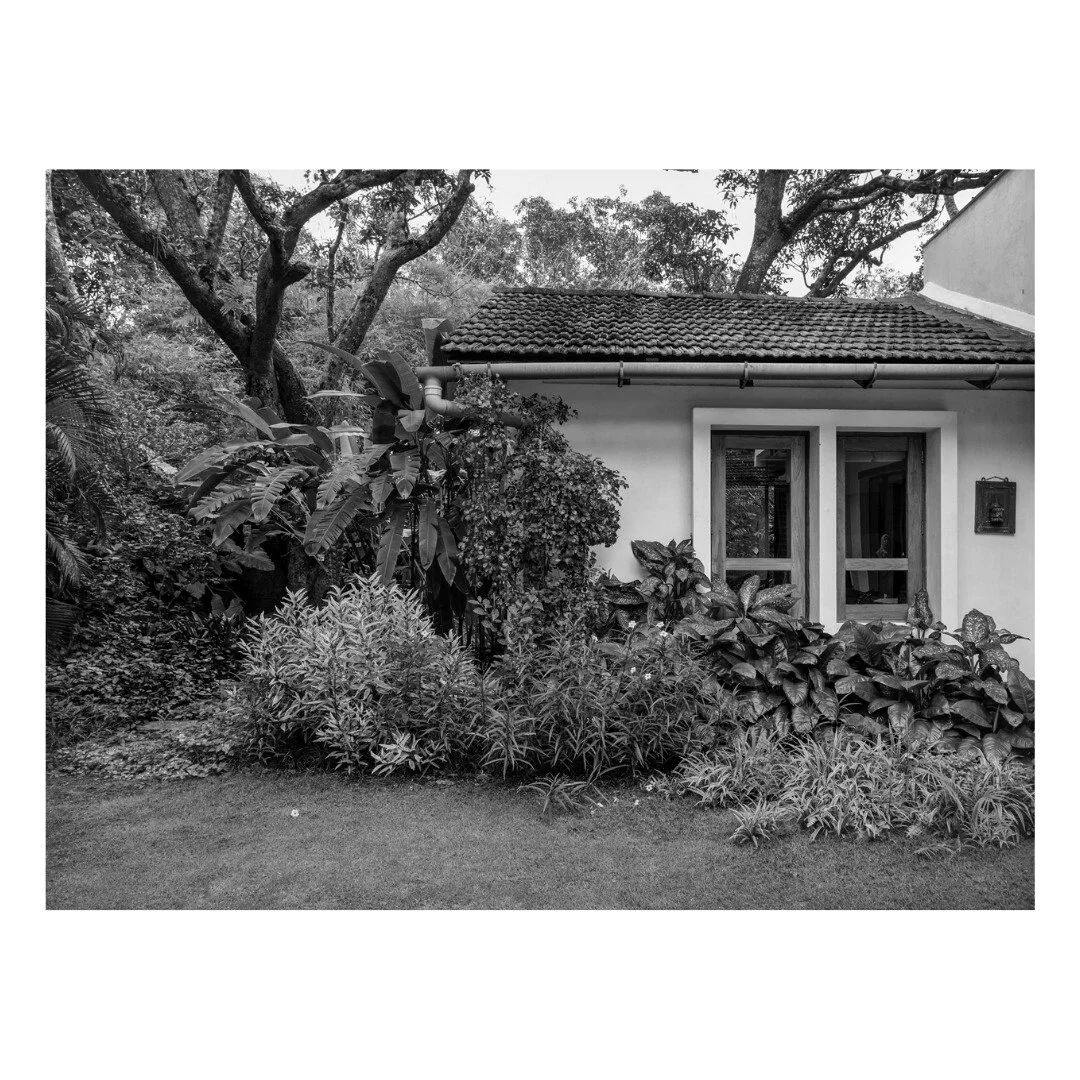

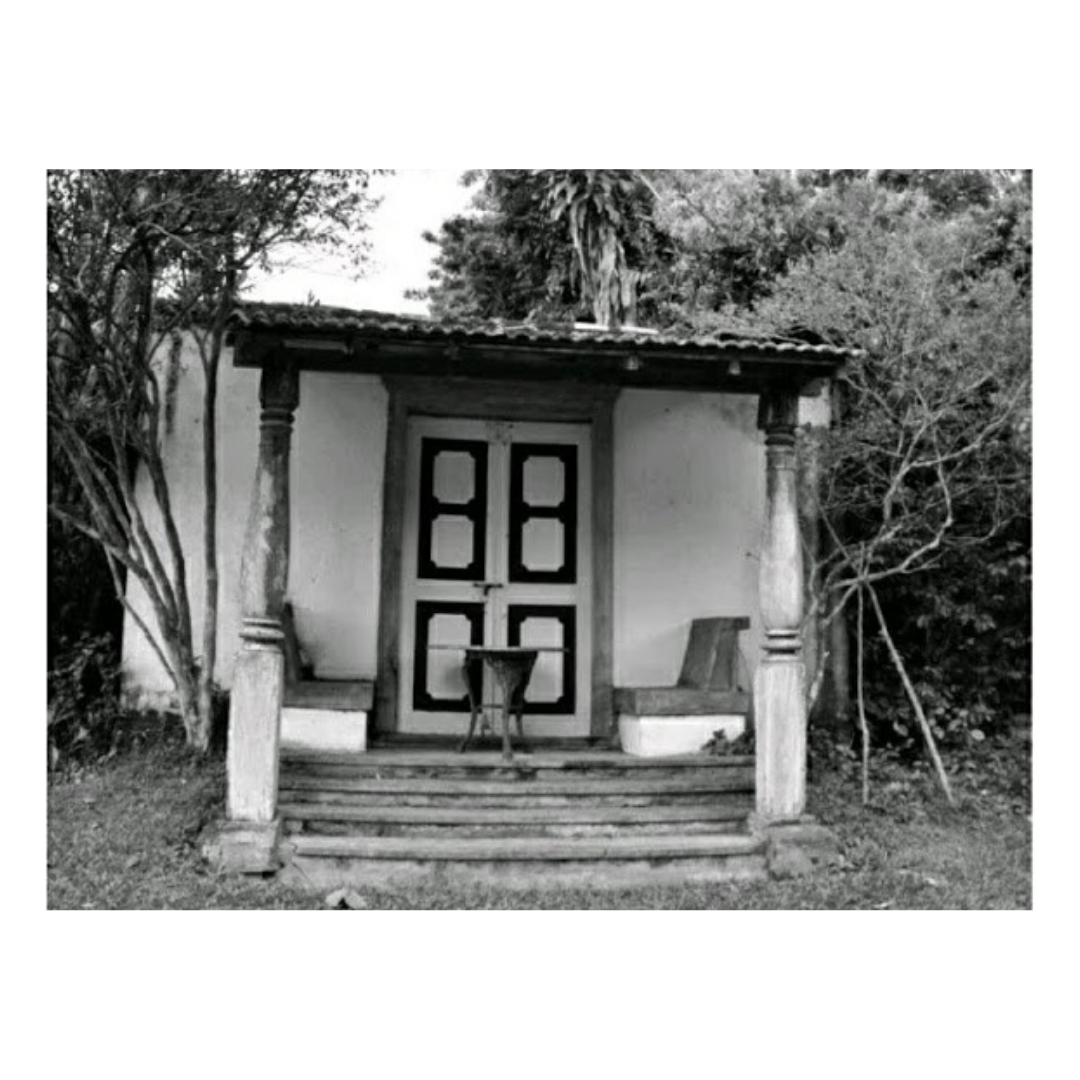

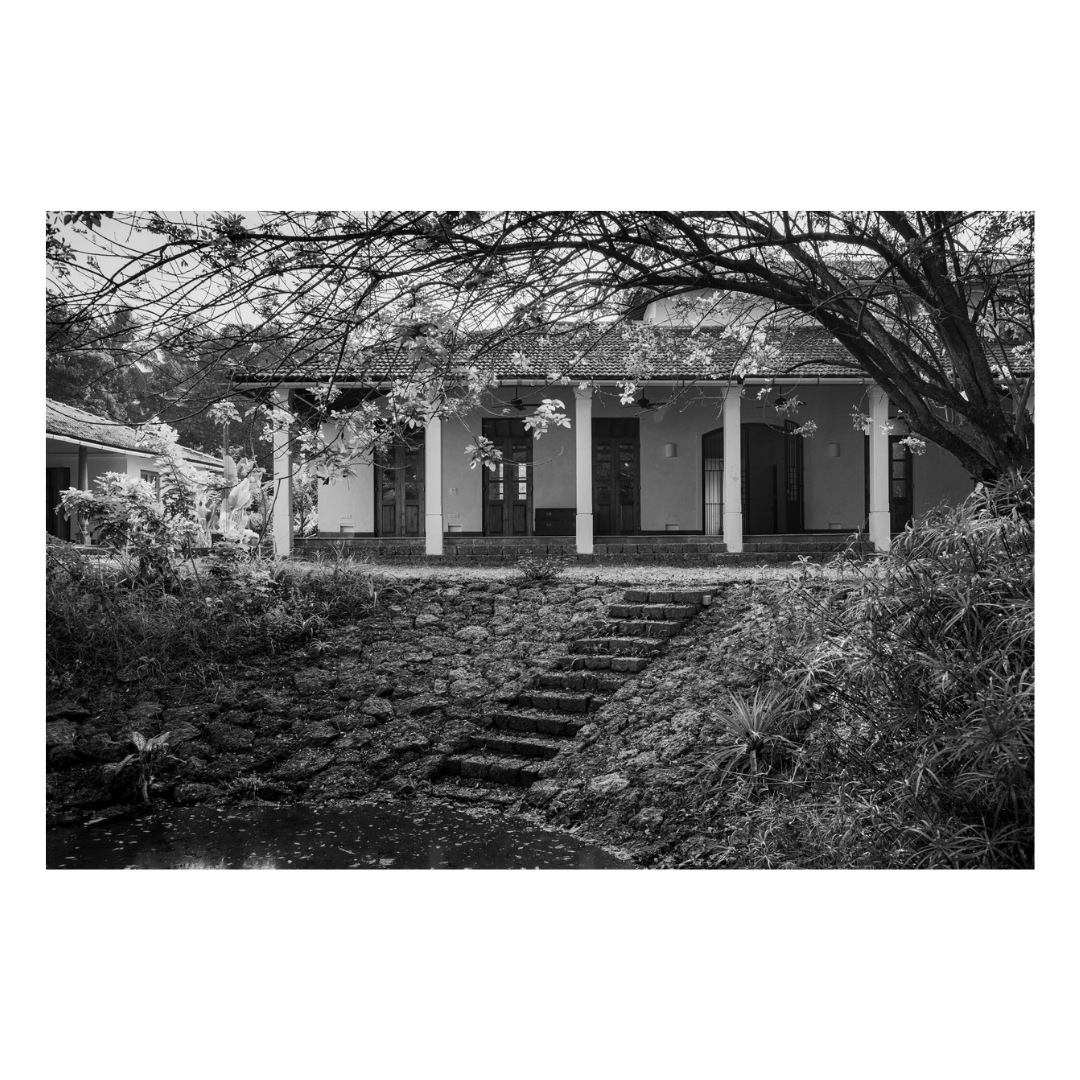

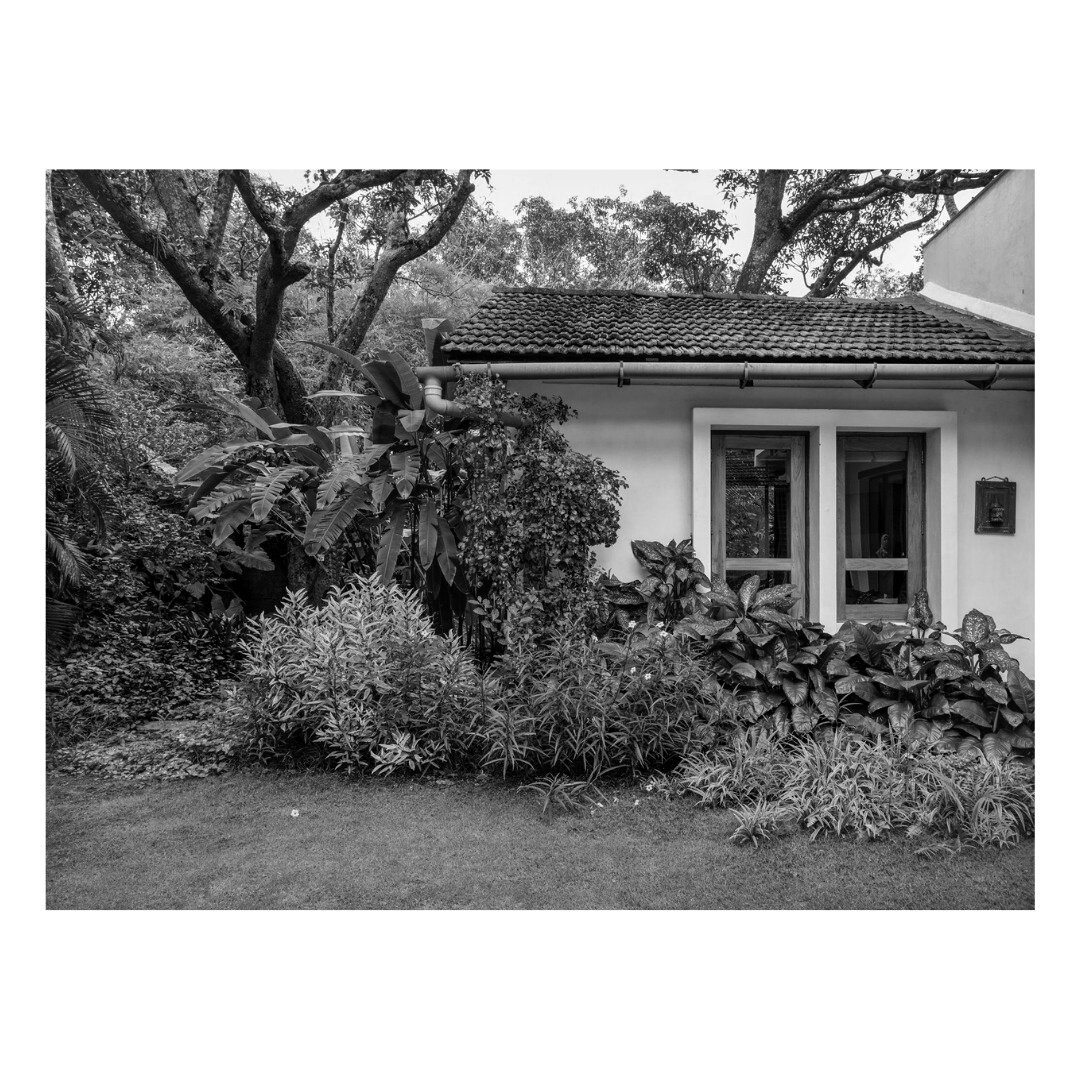

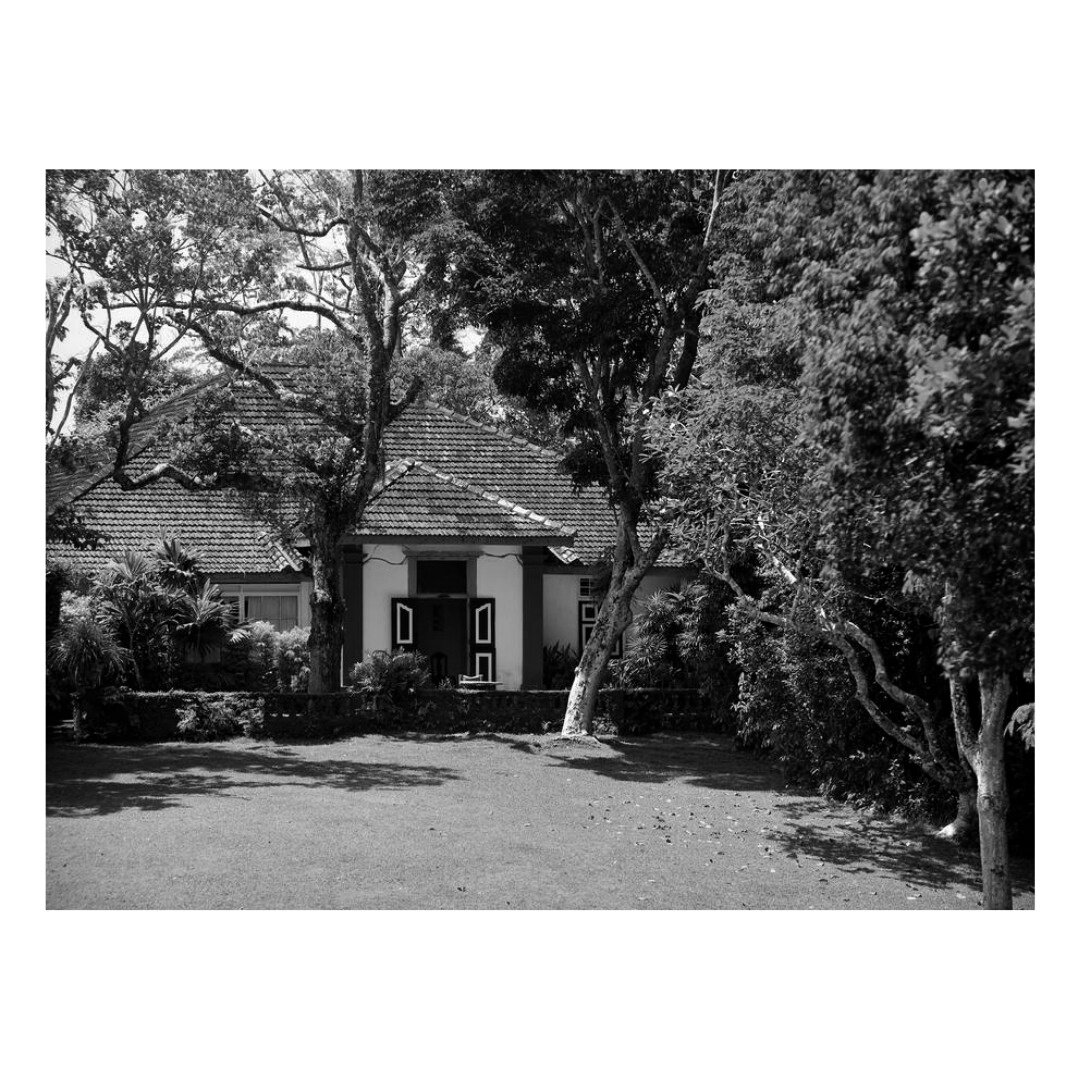

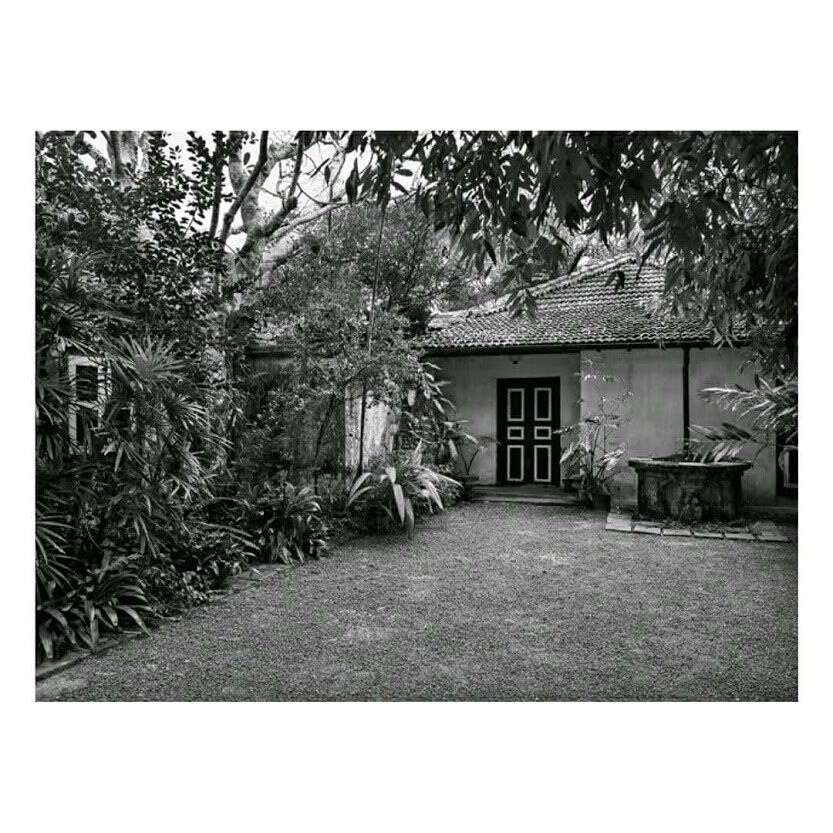

That said, certification is usually the starting point for us in our journey into sustainability. I firmly believe that ‘sustainability is common sense’. In architecture, it involves following sound design principles, respecting the land while planning new buildings and responding to the local climate and conditions.

To pursue sustainability,

we must try to conserve the natural resources within our own site (through rain water harvesting, renewable energy use and grey water recycling),

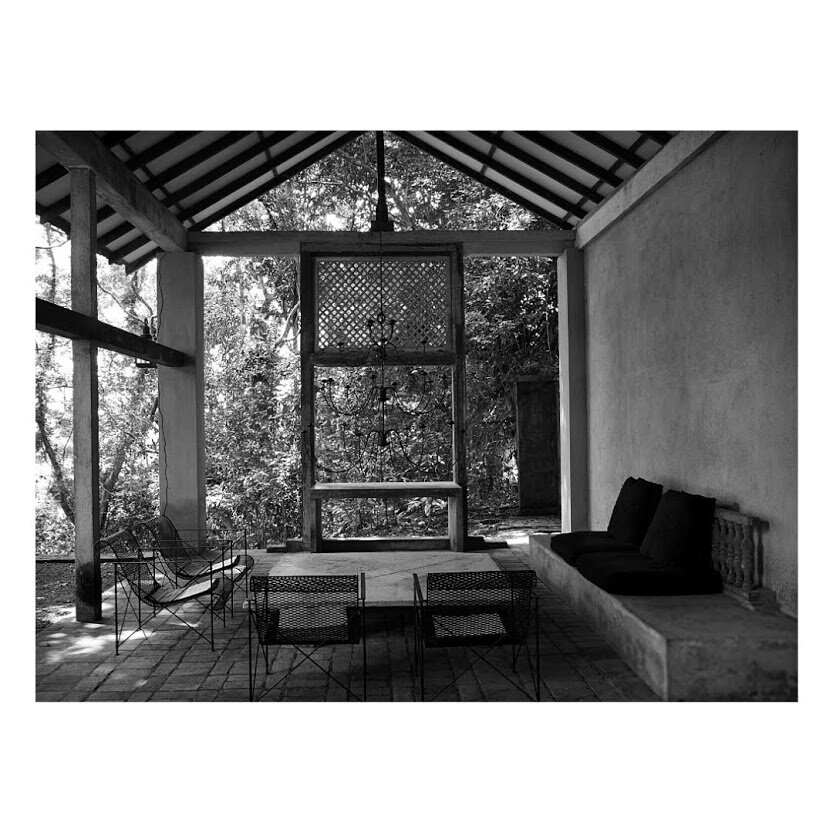

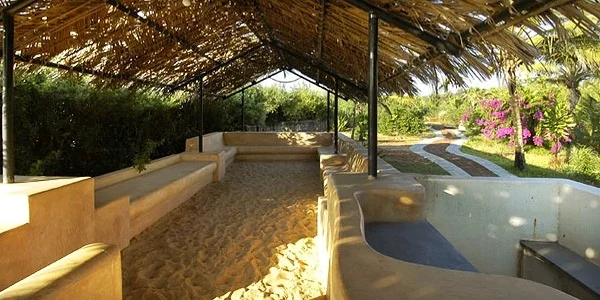

use materials and employ design ideas that keep the building interiors cool or warm (and reduce the use of air-conditioning and heating),

allow for ample daylight (to reduce the energy use for lighting during the day),

use half flushes in bathrooms along with aerators to reduce the water flow in bath and kitchen fittings (to reduce water-use),

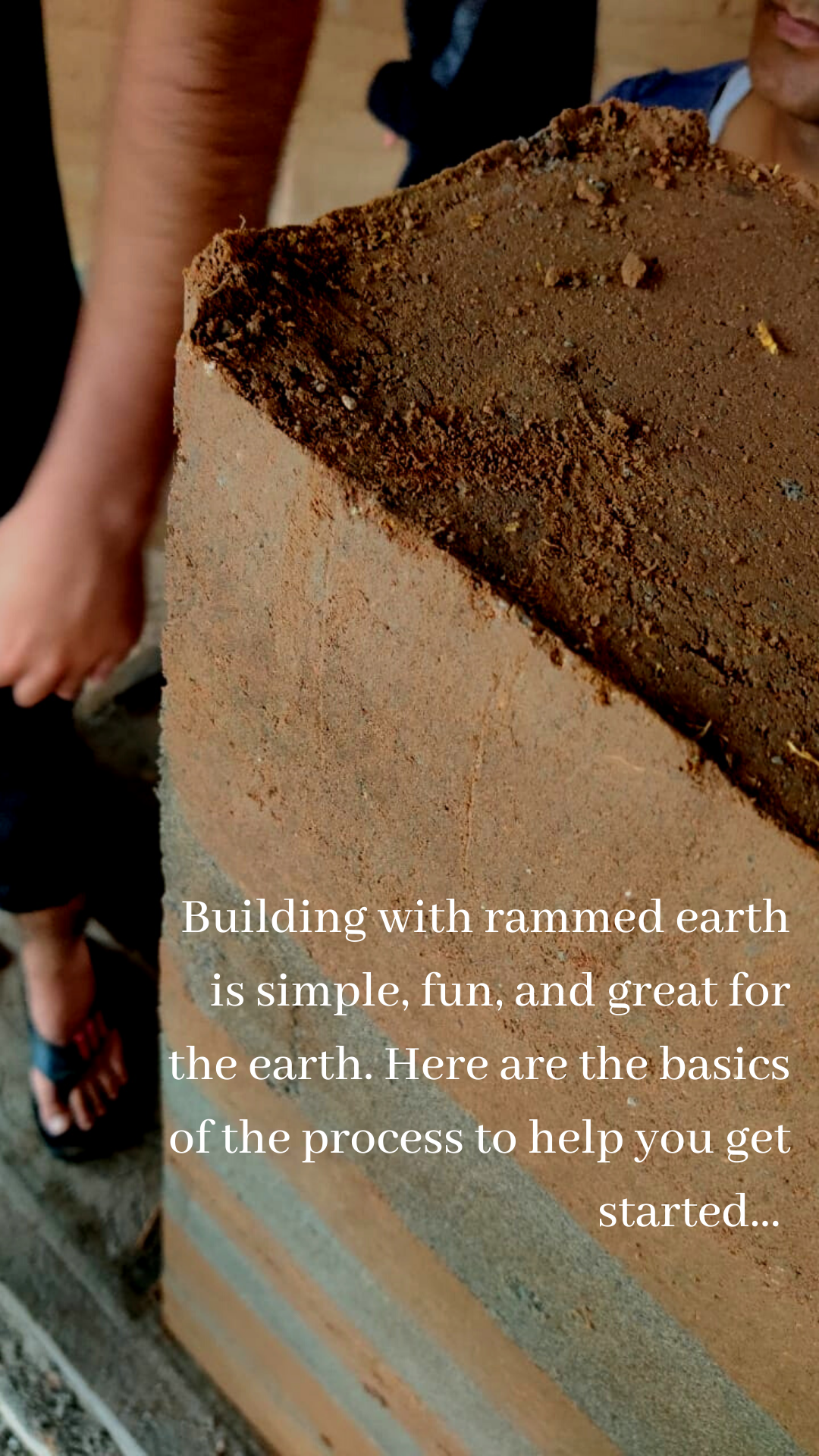

maximize the use of materials that are produced locally, and

use materials with a high recycled content.

These strategies for me are the low-hanging fruit that are easy to achieve with minimal cost escalation in the process. It’s also key to understand the lifespan of materials (regardless of their green features). If they have to be replaced in a short period of time, then they fail the test of sustainability. Finally, to achieve actual impact, we have to think about sustainability at every stage and factor it in every decision during the design and construction process.

LINKS TO PREVIOUS BLOG POSTS:

WHY BUILD GREEN

GREAT ONLINE RESOURCE FOR GREEN BUILDINGS IN INDIA

GREEN FEATURES AT NIVIM